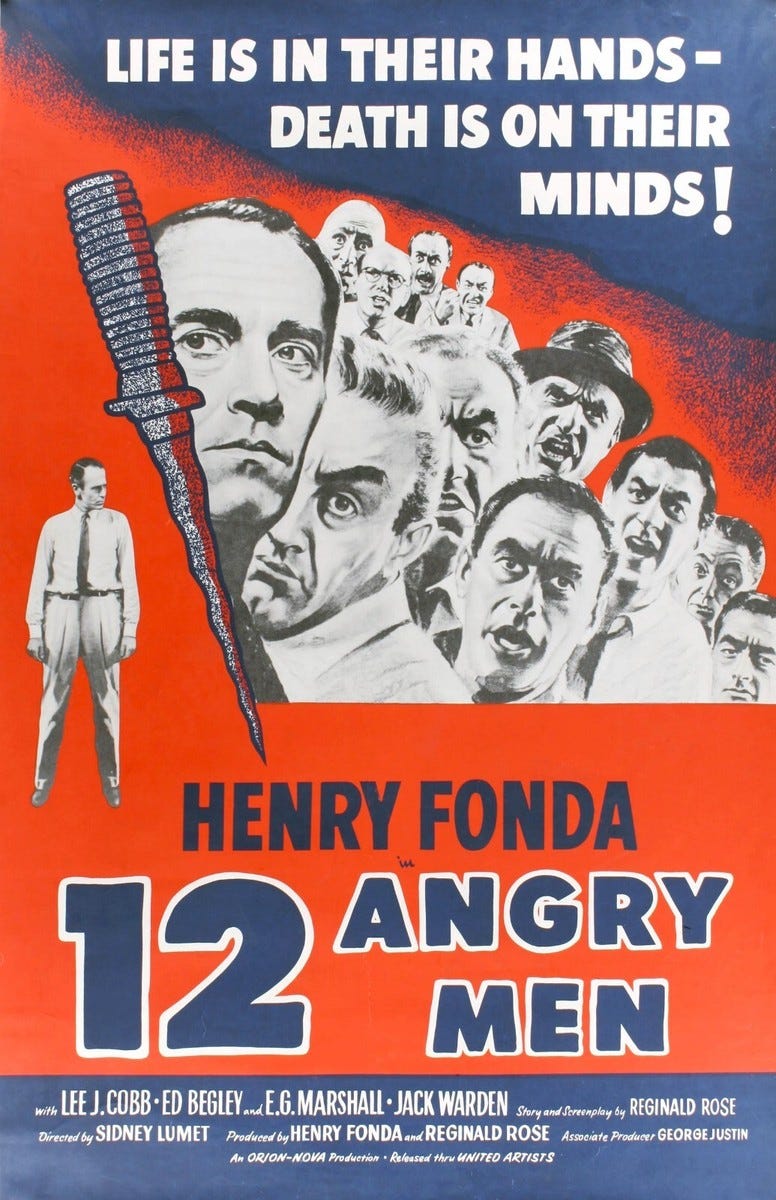

TALES OF LOHR: SIDNEY LUMET'S "12 ANGRY MEN"

A realist drama...or a fantasy about a system that works?; plus, "Factory Roll Call" skips to a Liu

Watching 12 Angry Men (1957), the chamber drama that earned first-time feature director Sidney Lumet his first of four Oscar nominations for Best Director, hits far different in the America of 2025. Since January 20, the federal government (such as it is) has essentially declared open warfare on the foundational legal concept of due process. Being an undocumented individual, which is classified in the American legal code as a misdemeanor (in other words, an action ostensibly regarded as bearing the same offense as an unpaid speeding ticket), is now being punished by masked mobs of unidentified men in slapped-together mail-order “uniforms” stealing said individuals off the streets and essentially disappearing them. An explanation has not been offered, and is not anticipated, for why, if the mandate of these brownshirts is to target hardened, dangerous criminals, the bulk of their raids are being conducted at such known non-hotbeds of crime as Home Depot parking lots, restaurant kitchens, and schools. An explanation has not been offered, and is not anticipated, for why, if the mandate is to punish solely those defying the rule of law, video after video has been captured of individuals claiming to be government agents grabbing people outside immigration court hearing rooms, people in the process of doing exactly what the conservative establishment has harped for years that they want these individuals doing “if they want to be left alone.” In order to enforce these nakedly hypocritical, obviously racially biased policies, the military has essentially been sent to occupy a city I lived in for over a decade. Their semi-official statement on the matter, delivered earlier this week by gestapo-coiffed “law enforcement officer” Greg Bovino after a force of soldiers and other “agents” bravely faced down the dire threat of children playing in MacArthur Park: “Better get used to us now. This is going to be normal very soon.”

All I can say is: Juror #8 would have called bullshit on all this in five seconds flat.

12 Angry Men, originally part of the New York theater-abetted tradition of realist ‘50s drama, now plays at least partially like a fantastical dispatch from an increasingly apocryphal America where the systems have held, where reason prevails over bigotry and vibes, where the concept of justice for all is not merely a smokescreen, but actually put into concrete practice. Screenwriter Reginald Rose, adapting his own 1954 teleplay from the anthology series Studio One, gives us a dozen jurors (yes, as the title states, they are all men, and all white; even reasonably progressive films of this period, such as this one, often conformed to the dramatic and social conventions of the time) faced with what they have been led to believe is an open-and-shut case. A Puerto Rican teenager has been accused of murdering his abusive father with a switchblade, a charge backed up by two neighbors, one who claims to have seen the actual stabbing, another who says he saw the boy fleeing the scene of the crime. The public defender’s work has been perfunctory at best. The judge’s instructions to the jury can’t even feign the appropriate amount of energy one would expect for a case that, as he plainly states, carries a mandatory death sentence if the boy is found guilty. The jury room, in which almost the entire film takes place, is drab. The day is unseasonably hot. The fan seems to be broken; the air conditioning is non-existent. And the initial trial vote finds 11 of the jurors ready to send this kid to the chair. Only Juror #8, played by evergreen salt-of-the-earth avatar Henry Fonda, has any sense of doubt. And over the course of a short, swift, enveloping ninety minutes or so, he uses logic, perception, and profound understanding of the minds of his fellow jurors to break down the evidence, reshape their views, and slowly, inexorably turn the tide of the case’s outcome.

(L to R, top to bottom: Martin Balsam, John Fiedler, Henry Fonda; Lee J. Cobb, E.G. Marshall, Jack Klugman; Edward Binns, Jack Warden, Joseph Sweeney; Ed Begley, George Voskovec, Robert Webber)

Rose’s script etches his dozen unnamed focal figures into concise archetypes of American masculinity at the center of the twentieth century, and Lumet’s cast, largely made up of performers then prominent in the New York theater scene of the moment, bring their own idiosyncrasies to their portrayals, resulting in a panoply of perspectives on the case facing them as a jury. As Lumet smoothly ushers the men into their places around the jury table, we are given glimmers of their private lives that tell us much about where their chips on the case will eventually fall. Some, like E.G. Marshall’s bespectacled stockbroker Juror #4, pride themselves on considerate reliance on nothing but the facts to shape their takes on the case, while others, like Ed Begley’s cold-battling #10, seem driven primarily by preconceived prejudices about the race of the defendant. Jack Klugman’s #5, himself a product of the kind of rough neighborhood in which the accused grew up, is torn between the evidence and what he knows to be unfair stereotyping of kids like this. #7, played by an avuncular-bordering-on-pushy Jack Warden, seems willing to bend whichever way the tide seems to be turning, provided it gets him out of the jury room and on his way to the Yankees game for which he’s got tickets. The character of the case is set into relief by the mere presence of George Voskovec’s #11, a polished, quietly classy watchmaker whose status as an immigrant upends many of the jurors’ easy assumptions. And then there’s #3, played by Broadway’s original Willy Loman, Lee J. Cobb. The most stubborn holdout on the jury, the one seemingly least willing to be swayed by logic and counterargument, #3 professes just as much detachment from his feelings towards the matter as Marshall’s even-keeled plutocrat. But that photo in his wallet…the one of him with his son…the son he hasn’t spoken to in two years…how is that swaying his take on this?

One of Rose’s canniest moves in conceiving 12 Angry Men is making Fonda’s #8 the juror about whom we arguably learn the fewest personal details. He reveals his profession as an architect in a restroom conversation with Edward Binns’ manual-laborer #6, and he is one of two jurors, along with Joseph Sweeney’s elderly yet razor-sharp #9, whose surnames we discover in the film’s final moments. But beyond that, all we know is that he’s a man trying to give a put-upon kid a fair shake, and determined that, if the verdict in which he participates is going to send that kid to his death, he’s going to be sure that it’s as close as possible to the right verdict, arrived at for as close as possible to the right reasons. It could be argued that, in removing #8’s personal stake in the verdict from the equation, Rose is diminishing the character, making him nothing but a mouthpiece for the writer’s philosophy. But #8’s unencumbered commitment to justice keenly shores up Rose’s points, while Lumet relies on Fonda’s gifts as an actor and speaker to carry the burden of making the character compelling even amidst his skeletal backstory. Fonda’s performances in films like Young Mr. Lincoln and The Grapes of Wrath offer grand testimony to his ability to find the humanity in characters that could have been mere talking-point generators, and 12 Angry Men gives Fonda a number of great chances to flex these muscles once again. He adeptly turns the words of stubborn jurors like Cobb against them; he knows when to step back and let bigots like Begley verbally dig their own graves; and his “gotcha” moment with a switchblade knife is one of the greatest moments in any legal drama. Juror #8 is not a flashy, ostentatious role when compared with the parts played by Begley, Cobb, and Warden; this might be why, even though the film earned Oscar nods for Lumet, Rose, and as the year’s Best Picture, Fonda was not among the acting honorees for his work here (as the film’s co-producer with Rose, he did share the Best Picture nomination). But he easily carries the burden of advancing the story while knowing just how to drop back in support. It’s a textbook piece of quality ensemble acting.

The film’s other smartest dramatic gesture is never making it apparent, to either the jurors or the audience, whether the defendant is in fact guilty or not. Juror #8 certainly offers convincing arguments against the prosecution’s evidence and witnesses, and the accumulation of counter-claims and #8’s sheer rhetorical skill eventually proves compelling enough to sway the entire rest of the jury to his point of view. But it is significant, in the midst of all of this, that #8 makes clear, again and again in explaining his points, that he’s not saying for sure that he knows the boy is entirely innocent. “I’m just saying it’s possible!” He repeats this assertion on several occasions, in the process carving in metaphorical stone one of the critical tenets of the American justice system: The power of the concept of reasonable doubt. Juror #8 is bound and determined to make certain that, if this jury is going to condemn this boy to death, there is no doubt, and no possibility of doubt, that he is indeed the one who murdered his father. And over the course of the film, he makes it clear to the rest of the jury not that the boy is indubitably innocent, but that it is entirely possible that he is. And “maybe he did it, maybe he didn’t” is simply not enough to hang a verdict on…especially one that will likewise hang the subject of said verdict. All of us, of course, have followed court cases, in the news or perhaps even in our own lives, in which, based on what we know about the cases in question, we disagree with the ultimate results of the jury. A major, highly publicized one just played out over the course of recent weeks, resulting in a ruling in the case of Sean Combs that many consider to be a miscarriage of justice. The flaws and fissures in the system this verdict, and others, reveal is a subject for a more legally astute newsletter than this one. But 12 Angry Men, at least, argues that “your day in court” is a virtue as sacred as any that our system can offer.

Which brings us, of course, back to my beginning. I personally have never served on a jury, but I am well aware of the conventional stance that it is a burden and irritation best avoided if possible. But after watching and thinking about 12 Angry Men, and considering the assault on the right to due process currently being carried out at literal gunpoint by ostensible guardians of justice…I’m not so sure I’d be as quick at this point as some to try to duck that responsibility. Jury duty is arguably one of our most direct means, as everyday citizens, of having a say in the proper maintenance of our system. And that’s something worth participating in…especially since, if the powers that currently, unfortunately be have their say, our days of doing so many be quite literally numbered. Even in 12 Angry Men, it would be difficult to argue that justice is entirely blind.

But I can tell you one thing I know for sure about her:

If she’s going to stay worth anything, she damn sure shouldn’t be wearing a mask.

NOTE: In 1997, working from an updated adaptation by Rose of his own script, William Friedkin directed a new version of 12 Angry Men that aired on Showtime. This rendition features Jack Lemmon as Juror #8, George C. Scott as #3 (winning an Emmy for his work here), and a far more diverse cast of jurors, including Edward James Olmos in for Voskovec as #11 and Mykelti Williamson as the bigoted #10. If you’ve seen Lumet’s version, I’d recommend checking this one out, too. It’s rock-solid.

FACTORY ROLL CALL

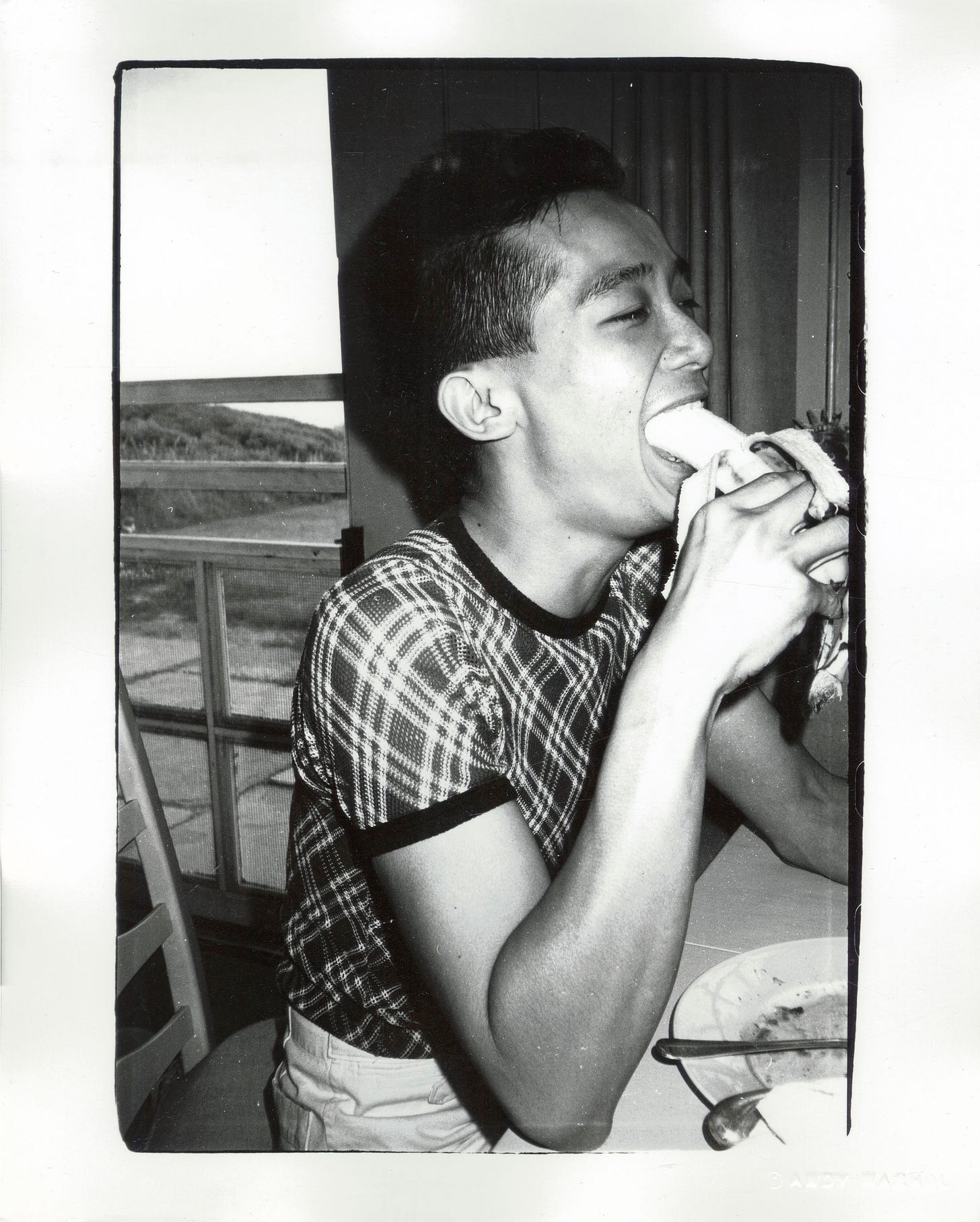

BENJAMIN LIU (1952 - )

Benjamin Liu was a relatively late addition to the ever-shifting extended cast populating the world of Andy Warhol, but he became arguably his most prominent day-to-day assistant during the final years of the Pop artist’s life.

Prior to taking on his responsibilities at the Factory, Liu was making his own marks on the downtown arts and club scene via his drag performances under the stage name Ming Vauze. These appearances allowed Liu to forge strong friendships with a number of then-emerging artists on the scene, including colorful Pop-influenced creator Kenny Scharf and graffiti-spawned iconoclast Keith Haring. Liu was supplementing his income working as an assistant to prominent fashion designer Halston and his mercurial, transgressive-artist lover Victor Hugo. Halston, of course, was a regular member of Warhol’s peripatetic nightlife retinue, and Hugo had been an intermittent, controversial, yet significant contributor to several of Warhol’s most important late ‘70s artistic series. Naturally, Warhol came into contact with Liu, and saw in the young man both an appealing work ethic and, more crucially, the kinds of connections to the key players of the downtown artistic moment that Warhol himself needed to forge if he hoped to maintain a position of prominence in the New York art scene.

Liu formally began working for Warhol in September 1982, and over the course of four and a half years forged a place for himself as the artist’s most central studio and personal assistant. His duties consisted of everything from toting along an umbrella during Warhol’s regular walks around the city (the umbrella was to keep both Warhol and his ever-present Polaroid camera shielded from the elements) to instrumental involvement in the packing and cataloging of the cardboard boxes of personal memorabilia and detritus that would come to be known, in later years, as the Time Capsules. And Liu did fulfill Warhol’s unspoken yet primary mandate for him, helping hook Warhol up with the likes of Scharf, Haring, and his most highly publicized “protege” of the ‘80s, Jean-Michel Basquiat. Noting a February 1985 New York Times article that branded Warhol the “Pope” of the young downtown arts contingent, Liu stated that his boss “was very aware of his role. He willed himself toward them.”

Longtime Factory veteran Brigid Berlin told Liu, upon first meeting him, that he was destined to be a Warhol “lifer” like herself. But Liu decided that he would stay with Warhol for only a limited time, setting for himself a departure date from his position of no later than Valentine’s Day 1986. Liu stuck to this plan, giving Warhol formal notice of his impending leave-taking a month before his planned out date. Nevertheless, after taking his leave, Warhol did manage to persuade Liu, on a fairly consistent basis, to drop by the Factory to help out with the occasional project…always insisting, of course, that his help would be called upon “just this once.”

In a way, Berlin’s prophecy regarding Liu has proved correct, as, since Warhol’s death in February 1987, the former drag artist has become yet another torch-bearer for Warholian history and anecdote, offering an especially valuable link to Warhol’s later life and career. Liu’s 1996 book Unseen Warhol, written with John O’Connor, features original interviews with a number of fellow Factory veterans, including early film superstar Baby Jane Holzer, longtime Interview Magazine editor Bob Colacello, and Silver Factory caretaker / jack-of-all-trades Billy Linich (aka Billy Name). Liu has participated in the opening and examination of several of Warhol’s Time Capsules, all of which are now part of the permanent archive at The Andy Warhol Museum, and in 2022, he appeared as one of the main talking heads in the Netflix docu-miniseries The Andy Warhol Diaries, which predominantly focuses on the period of Liu’s own years in the Warhol “family.”