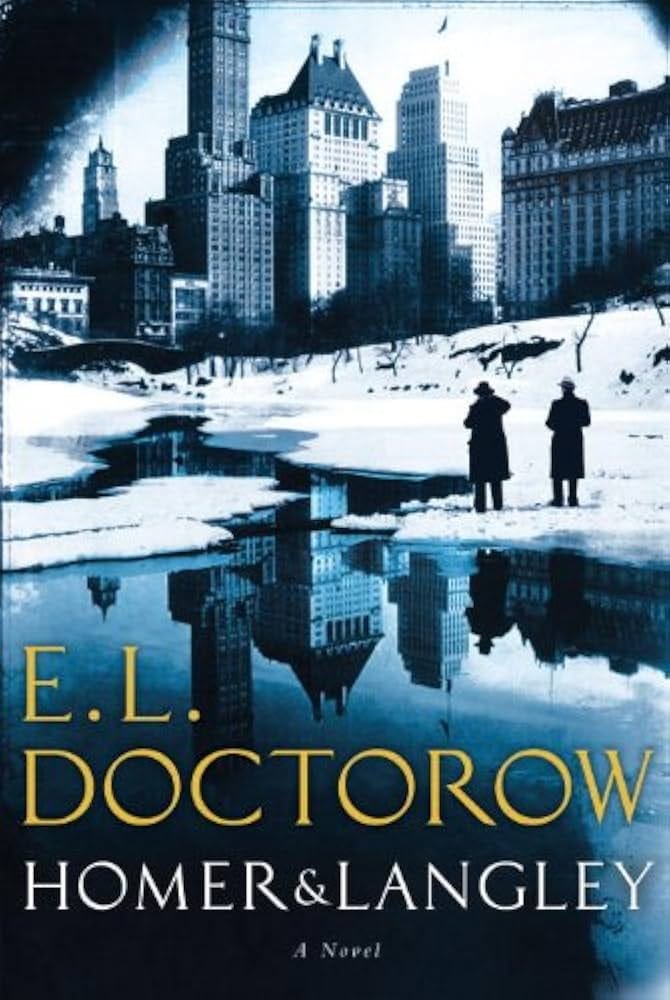

TALES OF LOHR: E.L. DOCTOROW'S "HOMER & LANGLEY"

A master muses on two American eccentrics; plus, "Factory Roll Call" just met a girl named De Maria

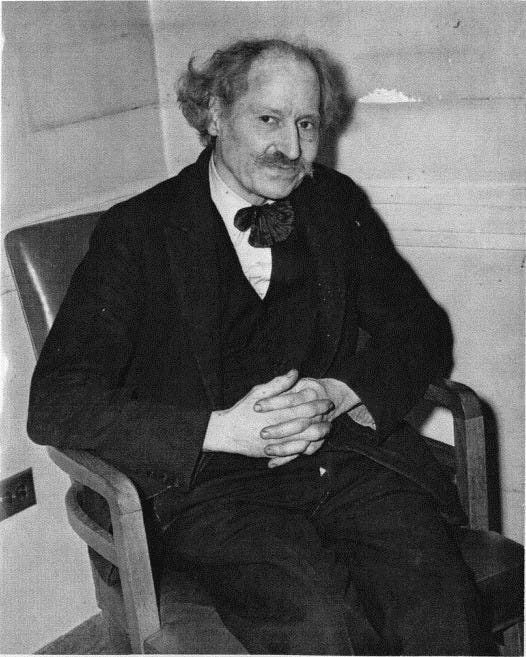

When I mentioned to my brother that I was reading a novel about Homer and Langley Collyer, a famous pair of sibling hoarders from early 20th century New York, he noted his own familiarity with the story, and summed up his perception of it in one word: “Creepy.” Indeed, it is easy, viewed from the perspective of an outside observer and with the distance of decades, to regard the unenviable strut and fret of the Collyer brothers as something out of a ghoulish troll-under-the-bridge fairy myth. Homer and Langley’s lives had begun with all the promise the reasonably prosperous can enjoy in America. Their father was a respected gynecologist based out of Bellevue Hospital; both brothers were college graduates; and Langley even took his skills as a concert pianist all the way to Carnegie Hall. But following the deaths of their parents (their father in 1923, their mother six years later) and four subsequent years of relatively regular engagement with the world at large, the Collyers began to withdraw into the warren of their Fifth Avenue brownstone in West Harlem. Some say their retreat from the world at large was a reaction to the changing demographic makeup of their old neighborhood. Many chalk it up purely to mental illness exacerbated by the trauma of parental death. Homer’s loss of sight, provoked by eye hemorrhages in 1933, further precipitated the brothers’ mutual hermitage, as Langley quit work to care for his older sibling full time.

And for fourteen years, all around their home, the Collyers amassed a trove, largely harvested by Langley during late-night neighborhood excursions, that would put the most egregiously troubled figures on the often horrifying reality series Hoarders to shame. Bundles of newspapers, mazes of boxes, bizarre home-improvement inventions of Langley’s own design, even a fully reconstructed Model T Ford began to overtake the once comfortable, reasonably stately home. Langley’s tinkering streak further extended to jerry-rigged booby traps designed to ensnare potential burglars or souvenir scavengers, as the house had become a favorite destination of curiosity seekers and gawkers. As the residence fell into ever-further disrepair and the brothers stubbornly rebuked all efforts at tax and bill collection, the Collyers eventually lost their electricity, water, and gas, and, in 1942, were threatened with foreclosure. This was staved off by Langley improbably producing a check for the entire remaining mortgage balance (equivalent in today’s currency to almost $129,000). Homer, sadly, had fallen into as much disrepair as the home in which he cowered, having added rheumatism-induced paralysis to his sightlessness; Langley attempted to “cure” his brother’s maladies via a series of quack diets and folklorish home remedies. On March 21, 1947, heeding complaints from a neighbor about a severe stench emanating from the house, emergency workers and police bulled their way through the morass and found Homer, starved to death in a small alcove dug through the trash. When Langley failed to turn up at the funeral, further excavation of the Fifth Avenue hoard uncovered his partially rat-eaten remains. He had triggered one of his own booby traps while bringing food to his brother, and been crushed to death approximately a week and a half before Homer succumbed. The junk salvaged from the Collyer brothers’ home after their deaths, amassed altogether, weighed a combined 120 tons.

So, for certain, a disturbing story with a grimly predictable conclusion. But the fascination of a tale like that of the Collyer brothers, I think, lies not in merely observing the oddity from a remove, but in attempting to plumb the psyches of individuals who, for whatever mental or spiritual reason, choose to transform the world in which they live into this bewildering miasma of implacable stuff. Author E.L. Doctorow, one of contemporary fiction’s finest dissectors of the American perspective, has tapped the inscrutable motivations of the Collyer siblings in Homer & Langley (Random House, 2009), and the resultant novel, short, brisk, enthralling, plays as an intriguing mirror image of arguably his most celebrated work, 1975’s Ragtime. Whereas this earlier book spins the immigrant and African-American experience of the early 20th-century U.S. into an expansive, prismatic, cast-of-many whirligig of entertainment, commerce, politics, and crime, Homer & Langley finds Doctorow attempting to filter similar concerns through the windows of a home occupied by a mere two men, one seemingly determined to both control and shut out the creeping influence of the march of time, another of great curiosity and desire to drink deep of life, frequently stymied by his own fragility and filial loyalties. The result is not a flawless work of historical fiction, but it engaged me, and weirdly moved me, as deeply as any novel I’ve read thus far this year.

(Pictured: Langley Collyer)

It must be said that readers whose judgment of a work of historical fiction lies principally in its fidelity to the truth will find Homer & Langley to be a deeply unsatisfactory read, as Doctorow, in shaping the Collyers’ story to his own concerns, has taken an honestly surprising number of liberties with the facts of the case. Homer was the elder of the two brothers by almost four full years; Doctorow makes Homer, the narrator of his novel, the junior sibling. His Homer, unlike the real Collyer who lost his vision at the age of 52, is struck blind in childhood, leaving Langley, the older brother in the author’s version, in his thus more logical caretaker’s role. Here, it is Homer, not Langley, who evinces a gift for musical expression; Doctorow has him primarily communicating with the world and his own spirit through the keys of his Aeolian piano, and even serving a brief stint as a silent-movie accompanist before talkies come in. And, in arguably the novel’s greatest digression from the facts of the Collyers’ case, the brothers, who in life died just shy of two years after the end of World War II, here live all the way into the ‘80s, observing both the Korean and Vietnam wars, the hippie revolution, the moon landing, even the 1978 cult deaths in Jonestown, all as their brownstone cage becomes increasingly intractable and unruly to manage.

Why, exactly, these liberties? I think it speaks to Doctorow’s intentions with these characters, and how he uses their feelings and reactions to the ongoing progress of the decades to come to terms with the strangeness of the circumstances in which they’ve entwined themselves. Homer, having been forcibly more constricted in his dealings with the world by his disability, nevertheless seems far readier to embrace much of the most elemental stuff of life. And not just music, although his discussions of his feelings for the sound (and the heartbreak of his realization, late in the novel, that his hearing is beginning to fail as well) are profound and palpably perceptive. Homer is also, by far, the more sexually inclined of the two brothers. He indulges in an ill-fated affair with one of the family’s servants; harbors amorous fantasies about one of his movie-house-days piano students who goes on to a doomed career as a Central American missionary nun; accepts a gangster acquaintance’s offer of an evening’s companionship from a prostitute far more readily than Langley; and even engages in a brief fling with a girl from a gaggle of flower children who squat for a while with the Collyers. These interludes would seem to fairly seriously undercut Homer’s status as a recluse. But they are always seasoned by Doctorow’s sense of Homer’s understanding of his diminishment, a feeling that resonates far more deeply later in the novel, when his chance encounter with a visiting French journalist ignites in him one last, futile-seeming urge to rejoin, as much as he can, the land of the living. As the pages creep on and Homer’s potential for escape becomes ever more remote, Doctorow burrows his observations further inward. “There are moments,” Homer says, in his always elegant self-expression, “when I cannot bear this unremitting consciousness. It knows only itself.”

Langley’s cross to bear, according to Doctorow’s vision of him, seems to be far too much knowledge of the world as it is, likely sparked by the author’s transformation of him into a veteran of the famously hellish First World War. His return from the charnel pits of the European conflict, followed not long after by the loss of his parents, seems to ignite in Langley something of a instinct to both forsake the world around him and, in his own way, contain and control as much of it as his powers can enable. His identity as the main accumulator of the Collyers’ junk indicates this desire to encompass the entirety of humanity within the brothers’ four walls. That Model T, parked as it is in the middle of what was once a well-turned-out dining room, suggests an impulse to freeze the world as he perceives it at a happier, more pleasant moment, before it all happened. His distrust of the outer world likewise manifests in his dealings with the innate uncontrollability of other people, relationships far more mercurial than Homer’s hopeful interactions. Langley’s brief marriage is almost comically doomed; he seasons his interactions with their gangster friend (who briefly uses the Collyers’ home as a secret recovery room following a nasty shooting incident) with a far greater degree of distrust than his brother; and in his generally dark pronouncements about his own species (“Christ,” he says, contemplating the atrocity of the Nazis, “what I wouldn’t give to be something other than a human being”). And all of this, his desire to make some sort of sense out of the universe that surrounds him, is encompassed in a project that consumes him throughout Homer & Langley. In life, Langley claimed to be constantly accumulating newspapers so Homer would have something to read in the quixotic instance of his eyesight returning. Doctorow’s Langley is using them as source material for something equally star-reaching: A possible Platonic-ideal paper that, in its gathering together of the only kinds of events that consistently recur throughout human history, would serve as the sole edition of any newspaper anyone would ever need to own or read. But even Langley cannot deny the hapless nature of his own quest, as he acknowledges that Homer and himself, “sui generis” as they are, render his perpetual-recurrence concept moot. But, rather than succumb to this truth, he games the paper to his idea’s advantage, telling Homer that, in its pages, “I’m obliged to ignore our existence.”

Still, for all Langley’s stubbornness, all Homer’s flights of escapist delusion, it is impossible to deny that, as Homer & Langley reaches its climax, Doctorow, in steadily contracting the narrative down to the brothers’ bare essentials, has pulled off something of unexpectedly immense power. Homer’s self-awareness of his plight, as he sets down his story in the forlorn hope that his maybe-returning French writer will read and understand, makes the increasing degradation of his circumstances difficult to weather. And his greatest fear, it seems, is simply being forgotten, his self figuratively buried under mounds of all too literal detritus. “…What could be more terrible,” he opines, “than being turned into a mythic joke? How could we cope, once dead and gone, with no one available to reclaim our history?” Thankfully, E.L. Doctorow was on hand, and despite the transparent liberties taken with his source, he has indeed treated the lives, objects, and souls of Homer and Langley Collyer as matter of the utmost seriousness. He has properly repositioned them within the historical record and the collective imagination, and as such, constructed as admirably affectionate a memorial to them as the pocket park that now stands on the former site of their magpie fortress. We will likely never fully understand the Collyer brothers, or why they lived and died as they did. But with this book, we can at least take a vicarious glimpse into their spirits. What is piled there is not always easy to grasp, but will be impossible to forget.

FACTORY ROLL CALL

SUSANNE DE MARIA (aka Susanna Wilson) (1940 - )

As a fan and attentive student of the minimalist movements in art, dance, and music in early 1960s New York, Andy Warhol could frequently be found attending performances at the loft of composer La Monte Young, whose Theater of Eternal Music was noted for works that relied on intensely sustained sonic meditations on single notes. At one of these stark recitals, in 1964, Warhol met Susanne De Maria. A California native educated at Berkeley, the artist, dancer, and model was then married to her college sweetheart Walter De Maria, a sculptor and installation artist who would, later that year, serve as the short-lived first drummer for a band then featuring fellow artist Tony Conrad, Welsh-born sometime Young collaborator John Cale, and a well-read yet standoffish fellow named Lou Reed. (The band, with first Angus MacLise and then Moe Tucker on the drum stool, would become the Velvet Underground; De Maria is today arguably best known for the Earth Room, an ineffably affecting 1977 art installation that stands to this day in an otherwise unprepossessing Soho office space.)

Warhol was struck by De Maria’s beauty and, as he often did when confronted with particularly attractive people, invited her to appear in one of his films. But when his proposed on-camera scenario for her involved having unsimulated sex with a stranger (for his often quite explicit omnibus feature Couch), she refused. Warhol was forced to content himself with shooting a pair of Screen Tests. He eventually featured these reels in several iterations of his malleable multi-Screen Test program known as The Thirteen Most Beautiful Women, including a version of the film licensed to air on German television in 1969. Copies of this TV print made their way to both London and Paris, likely explaining how an unauthorized frame grab of De Maria found its way onto the front cover of a German-pressed album by Skyline, an apparent cult favorite of club and dance music aficionados that dubiously credits the New York Dolls’ Johnny Thunders as its guitarist.

In addition to her brush with the Warholian spotlight, De Maria and her husband co-operated a gallery on Great Jones Street in Manhattan. This space would regularly play host to happenings curated by avant-garde theater innovator Robert Whitman. De Maria performed in a number of these events, and also turns up in a few of Whitman’s “Cinema Pieces,” most notably 1962’s Dressing Table. She can also be seen in 1968’s No President, a topical burlesque film by occasional Warhol star and influential performance artist Jack Smith; she occasionally modeled for Smith’s efforts as a photographer as well.

Following her separation from Walter (she has since undergone another marriage and divorce), De Maria changed her professional name to Susanna Wilson. Throughout the 1970s, she made her principal living as a fashion designer whose line, O’Susanna, graced the shelves of Bloomingdale’s, Saks Fifth Avenue, and other quality clothing boutiques. O’Susanna also offered a fragrance line, its best-known scent being the strong-selling Strawberry Love. She later settled in California, where she worked a lucrative stint as a publicist. In 2011, Wilson, then residing in Grass Valley, California, was featured in a New York Times article discussing her precarious yet relatable situation as an older homeowner with no savings. No current update of her circumstances is readily available, but as far as can be determined, Wilson is still living, presumably in north central California.