TALES OF LOHR: "BLACK POWER 'WE'RE GOIN' SURVIVE AMERICA'"

Leonard M. Henny makes a choice that speaks volumes; plus, "This Week in Warhol" flips the tassel

FREE HUEY!

The motivating impetus behind one of the most iconic American resistance slogans of the late 1960s was the arrest, on October 28, 1967, of Huey Newton, co-founder of The Black Panther Party. Birthed out of activist circles in Oakland, California, the Panthers spearheaded dozens of community support and personal improvement initiatives, most famously a free breakfast program that fed thousands of poor kids during its operation. The Panthers achieved all this while under intense scrutiny, and often open persecution, by both local law enforcement agencies and the FBI. Newton, an eloquent autodidact whose personal philosophies springboarded from early encounters with Plato’s Republic, was a particular target of J. Edgar Hoover’s ire, as was really any self-possessed, assertive Black man who wouldn’t simply buckle under to the establishment’s will. Following an early-morning police stop in Oakland, Newton and a friend became involved in a shootout with police, during which Officer John Frey was killed. Despite accounts that Newton was already under arrest when the gunfire broke out, he was taken into custody to await trial for murder.

On February 17, 1968, Newton’s birthday, activists and community members gathered for a rally at the Oakland Auditorium. In addition to commemorating their imprisoned comrade, the event marked the official merger of the original Oakland chapter of the Panthers with the Black activist-spearheaded Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee. Though this tumultuous connection would last a mere six months, the event kicked off the organizations’ union in powerful fashion. Among the principal speakers were H. Rap Brown, the Panthers’ minister of justice, and Stokely Carmichael (aka Kwame Ture), the charismatic and controversial former chairman of the SNCC. Carmichael’s speech, a roiling, incendiary statement rendered with equal parts fury and righteous indignation, was captured on film by Dutch sociologist / documentarian Leonard M. Henny, and it forms the aural centerpiece, and half the visual focus, of the short film Black Power “We’re Goin’ Survive America.”

The latter part of Henny’s title is a quote from Carmichael’s speech, and it captures both his easy incorporation of African-American Vernacular English and his way with a turn of phrase that roots both his words and their animating philosophies in the listener’s memory. Throughout his remarks, primarily framed by Henny in a stark medium left-profile shot that isolates Carmichael at a bank of microphones before a sea of deep black, the speaker boldly calls out the injustice that undergirds all of American Black life and, far too frequently, lashes out in pointed, elevated hostility and violence. He equates the Black struggle in America with the country’s campaign of genocide against the country’s indigenous people; as he asserts the white man’s desire to essentially wipe out Native America, he repeats, several times for emphasis, “And he did it!” This triplicate repetition of phrases links Carmichael’s rhetoric to the techniques of Black preaching, and evinces the same effect, as can be heard and seen in the enthusiastic ovations that regularly greet his pronouncements. Carmichael is unsparing in his critique of white oppression and disenfranchising actions, contrasting these dark hostilities with the “undying love for our people” he finds exemplified in the actions of Newton and the Panthers. He forcefully advocates for Black control of the education systems that teach their children the ways and truths of American life, and he openly calls the Black struggle a necessarily international movement. As his speech builds to its climax, Henny hits hard with Carmichael’s now-legendary (or infamous, depending on your point of view) final words:

…brothers and sisters, brother Huey P. Newton belongs to us. He is flesh of our flesh, he is blood of our blood. He may be Mrs. Newton’s baby; he is our brother…We do not have to talk about what we’re going to do, if we’re consciously preparing and consciously willing to back those who prepare. All we say: Brother Huey will be set free. OR ELSE.

In assembling Black Power “We’re Goin’ Survive America,’” Henny makes a simple choice that lifts his film out of the realm of newsreel and formally positions it as a piece of art. This is his decision to intercut the visual record of Carmichael’s speech with images of a dance performance, at the same rally, by the Uzohi Aroho Dancers and Company, and the Birth of Soul Dancers. Backed by a small African percussion ensemble, the dancers, beautiful Black women in vibrantly patterned garb, undulate, spin, and bend, a vivid visual counterpoint to the coolly driving beat. We can see that this dancing is not occurring during Carmichael’s speech; the podium at which he delivers his address is clearly visible on the stage alongside the dancers, unmanned. But Henny continuously tracks the audio of Carmichael over the footage of the dancers, thereby linking the activist’s passionate community-elevating rhetoric with the creative expression of the artistic performers. This force, this rage, this determination, Henny’s editorial choice seems to suggest, flows from the same cultural wellspring that guides these dancers through their beautiful, welcoming display.

Henny further reinforces the unity and fellow-feeling of the event via his images of the appreciative Oakland Auditorium audience. While his footage of Carmichael is shot in black and white, both the dancers and the crowd are primarily in color, and though the grainy, handheld 16mm images perhaps don’t do full justice to the kaleidoscopic energy of the audience members, they capture enough of the exhilarating patterns and color combinations of the wardrobes on display. Many of the women adopt traditional adornment, head wraps, and flowing dress, and the regal figures they cut support Carmichael’s assertion of the grace and might of Black culture. Most of the men are more sedately attired (the Black Panthers we see in the crowd are of course in the classic black-jacket-and-beret ensemble, most also sporting black sunglasses), but there are a few noteworthy pops of color in their outfits as well. I will never forget the impact of two quick images of a standing man seen from behind, the richness of his crimson blazer fully displayed by his extended arm, upraised in a Black Power fist.

Watching the defiance and resplendence in view throughout Black Power “We’re Goin' Survive America,’” it is sobering to reflect on what would befall many of the key figures upon whom the film’s focus lies. Carmichael would be out at the SNCC before the year was over, but would continue his career as an activist and lecturer before dying at the age of only 57, felled by prostate cancer. Newton was indeed convicted in September ‘68 of the murder of John Frey, but after several years of appeals and multiple hung-jury retrials, he was eventually set free. Amidst his own ongoing activism, his latter decades were a complicated morass of further trials and accusations of violence, exacerbated by an increasing drug problem; he was murdered in 1989, at just 47 years of age, by an aspiring crack kingpin. Brown, unseen in Henny’s film but a key speaker at the event presented onscreen, is now Jamil Abdullah al-Amin, 81 years old, and currently serving a life sentence related to the shooting death of two sheriff’s deputies.

And still Black bodies wrongfully fall, and dancers dance, and filmmakers capture as much as they’re able.

Huey may have gone free, but freedom for Black people in America is always conditional. Black Power “We’re Goin’ Survive America’” is a reminder of that fact, those stakes…and all that we could lose if the Powers that Be end up having their ultimate way.

Black Power “We’re Goin’ Survive America’” is available for streaming rental through the official website of the Film-Makers’ Cooperative. To learn more, or to stream the film yourself, visit the Film-Makers’ Coop’s Vimeo channel.

THIS WEEK IN WARHOL

JUNE 16, 1949

The College of the Arts at Carnegie Tech, the Pittsburgh-based college that, in 18 years’ time, will become Carnegie Mellon University, holds its 52nd commencement ceremony at the city’s Syria Mosque performance venue, in the same neighborhood of Oakland that the school itself calls home. Among those receiving their degrees this day, taking home a Bachelor of Fine Art in Pictorial Design, is another Oaklander: Andrew Warhola, who has just recently begun dabbling in crediting his canvases and other artwork to the slightly altered sobriquet Andy Warhol.

Warhol attends Carnegie Tech via the partial support of a series of postal bonds purchased by the budding artist’s father, who earmarks the proceeds for his youngest child’s ongoing education prior to his premature death in 1942. Residing at his boyhood home in the South Oakland area of the neighborhood during his matriculation, Warhol at first makes a bumpy transition to higher education. He is actually threatened with a failing grade in his first year, due to his purported poor draftsmanship skills. He saves his academic hide via an independent project in which he creates quick, energetic sketches of South Oakland patrons of his brother Paul’s produce truck. These works win Warhol the school’s Martin Leisser Prize, an award for student art produced outside the classroom, and the pieces are displayed in a campus gallery, the first-ever public Warhol exhibition.

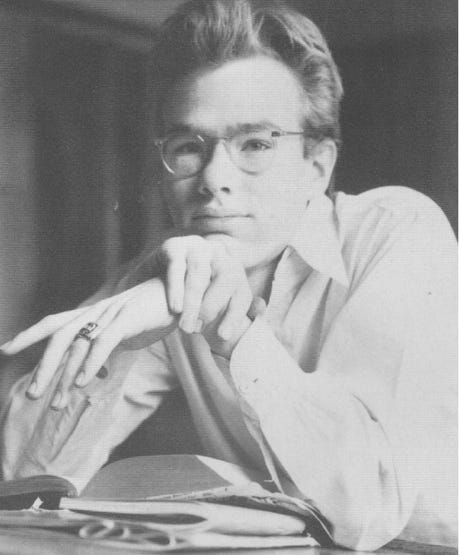

Over the next three years, Warhol emerges as a standout student in the Carnegie Tech arts department. His instructors hail his idiosyncratic vision, and praise him for being alone among his peers in having “something to sell.” He further hones his creative sensibilities via off-campus work at a converted barn studio he shares with a fellow student, painter Philip Pearlstein, and through a summer job as a window-dressing assistant at the Horne’s department store in downtown Pittsburgh. Warhol is the only male member of Carnegie Tech’s Modern Dance Club, though his skills are mainly put to work designing advertising materials and program covers for the club’s events. Another classmate, Jack Wilson, also notes that in 1948, Warhol assists with his first foray into filmmaking; Wilson describes the piece as “a parodic film about one of their professors that involved fast-paced comic encounters, mock murders, and chases through the city.”

Shortly before his graduation, Warhol causes his first significant arts-related controversy. His submission for the Associated Artists of Pittsburgh’s annual juried exhibition, presented in his last semester at Carnegie Tech, is a rough-edged, vulgar painting called The Broad Gave Me My Face, But I Can Pick My Own Nose. Over the objections of a prominent juror, German social-critic painter George Grosz, Warhol’s canvas is rejected by the exhibition, though he later presents it as part of a separate student exhibit under the less confrontational title Don’t Pick On Me.

Less than a month after Warhol’s graduation, he and Pearlstein board a train to New York City, where they plan to secure an apartment together as they pursue their artistic ambitions. Pearlstein goes on to become one of America’s most celebrated mid-century realist painters. Warhol, who will live in New York for the rest of his life, forsakes his educational background during numerous interviews, occasionally going as far as to suggest that he never even completed high school. Nevertheless, Warhol, like Pearlstein, achieves some success as an artist, too.